My first visit to Faribault Woolen Mill was a little over seven years ago. As part of an intro-to-production training, I ventured to the mill with around twenty of my peers, eagerly anticipating what the day-to-day in a factory would be like.

Raw white and black wool is processed and spun to create grey yarn.

Raw white and black wool is processed and spun to create grey yarn.

If I recall correctly, we, the business-analysts-in-training, outnumbered the team working at the mill that day and the mill was producing only a handful of different blankets. It felt slow, almost as if everything had stopped just for us, although I know now that that wasn’t the case. Nonetheless, we were given an entirely thorough tour – the team proudly explained how they turned raw wool into yarn and then wove said yarn into blankets, and thoughtfully answered our questions about production, lead times, and the like.

Combing the white & black wool.

Combing the white & black wool.

I left thinking I knew how a factory worked. I also remember thinking that it was ironic that a company that we would never work with was taking the time to teach us – the people who would soon be importing products from everywhere in the world except from this mill in Minnesota- about production.

The mill is fully integrated, which means it can accomplish all production steps, from raw wool to finished goods. It is the only mill of it’s kind left in the United States… pretty incredible, right?

The mill is fully integrated, which means it can accomplish all production steps, from raw wool to finished goods. It is the only mill of it’s kind left in the United States… pretty incredible, right?

Since then, I’ve visited factories all over the world but the simple pride displayed during my first visit to Faribault has always stuck with me. I became accustomed to factory tours where the teams would boast about the state-of-the-art equipment or the multiple production shifts ensuring product flow was consistent, but I never again saw a factory where the team was solely focused on – and proud of – preserving their craft and working with what they had. I knew they existed, but I wasn’t lucky enough to work with them.

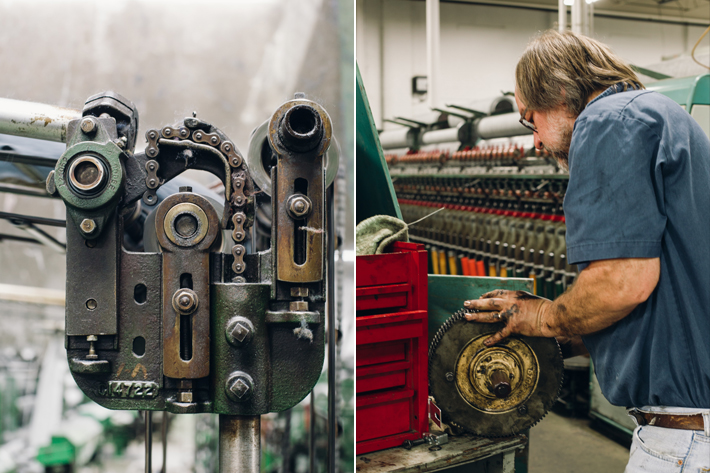

Most of the machines are from the 1940s-1960s and many are no longer produced, so the teams conduct proactive maintenance to ensure they remain viable.

Most of the machines are from the 1940s-1960s and many are no longer produced, so the teams conduct proactive maintenance to ensure they remain viable.

It felt like I’d come full circle when I visited Faribault again a few weeks back. I first visited to learn about production, to utilize the knowledge I gained to import product. Now I was there as a friend, with a goal of sharing the experience with you and celebrating the brand that Faribault has become. I’m a factory nerd at heart – the daughter of an engineer and a scientist/maker, I love to see how things are made. But to say that my most recent visit to Faribault was powerful is not quite enough.

Yarn!

Yarn!

Faribault is more than a mill; it is an incredible, proud community. That pride and sense of community is why I was given such an outstanding tour years ago, even though my work was indirectly responsible for the change in consumer behavior that had put the mill in danger of closing. And that proud community, combined with hard work, calculated risks, and a belief in heritage values and production, is why Faribault is what it is today.

Yarn is spun onto spools for use on the looms.

Yarn is spun onto spools for use on the looms.

It wasn’t easy. The mill, which had been open since 1865, closed in the middle of the workday in 2009 – the middle of the day! Can you imagine? The machines were tagged for sale to a company in Pakistan, and the building sat unused for two years, managed by a devoted caretaker who remains integral to Faribault operations today. In 2012, the mill was purchased by Chuck and Paul Mooty, local businessmen who believed in the brand and the value of made-in-America products and who understood that the rising price of wool overseas could make domestic production advantageous again.

Yarn storage in the mill.

Yarn storage in the mill.

The mill had flooded while closed, and no one could be sure the machines were still operable, but the Mooty’s took on reparations, updating the building, servicing the machinery, and adding new machines to modernize the process as needed. But they did not do this alone – when the plan to reopen the mill was announced, the craftspeople began to return. After the mill shut down, some employees had taken early retirement and others began new careers – many ended their retirements in order to return to Faribault, and one woman who was a few degrees short of completing a nursing degree even chose to forego the degree in order to return to the mill! The mill had been, and continues to be, a multigenerational family operation, and the employees were committed to it’s revival. They returned to rebuild the mill and the brand and to establish processes to ensure Faribault would be successful going forward.

This early 20th century typewriter is used to transmit patterns to the looms.

This early 20th century typewriter is used to transmit patterns to the looms.

And it has been. The timing was apt, of course, given the resurgence of the made-in-American movement and of conscious consumerism, but most importantly, the new team behind Faribault stayed true to their heritage and continued to put out incredible, classic products. Today, we see Faribault at Steven Alan, at West Elm, at all of our favorite boutiques and in GQ and Martha Stewart… which means that the once quiet mill now employs almost 100 people and runs production lines each day.

Sometimes, I wonder if this site is worth it. I worry that, at the end of the day, TAE is still just pushing latent consumerism and can do little to change consumer behavior. This trip to Faribault was so powerful and reaffirming because I remembered (again) that it’s not about buying stuff. It’s not about having all the things. It’s about community, and family, and heritage, and following through on your beliefs and values. It’s because the why and the how are just as important as the what.

Sometimes, I wonder if this site is worth it. I worry that, at the end of the day, TAE is still just pushing latent consumerism and can do little to change consumer behavior. This trip to Faribault was so powerful and reaffirming because I remembered (again) that it’s not about buying stuff. It’s not about having all the things. It’s about community, and family, and heritage, and following through on your beliefs and values. It’s because the why and the how are just as important as the what.

Without the Mooty’s belief in Faribault, and without the craftspeople and brilliant strategists who returned to rebuild the business, and without the retailers who believed in the brand and the consumers who chose to buy this incredible product, we wouldn’t have a story. But because of all of these people, because of this community, we do. And that is what makes it worth it.

The factory store

Original photography for The American Edit by Ashley Sullivan. Follow Ashley on Instagram!

Thank you to Bruce Bildsten and Jana Woodside for sharing the Faribault Mill story and taking us on the tour. Follow Faribault:

Line Drawings :

Line Drawings :